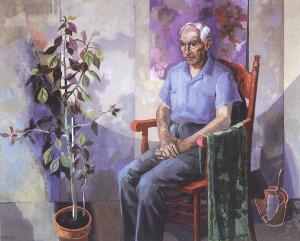

Portrait of Papa

Hands down one of my all time favorite paintings and it happens to be by my Father. It’s his painting of his “Papa”. At one point the painting reminded me of Andrew Wyeth’s “That Gentleman,” also in the Dallas Museum of Art’s collection. My father would have scoffed at that notion but it certainly had the same feeling.

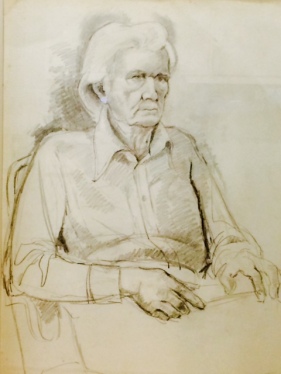

I said, “At one point” because when I went off to college it had been hanging in the house for some time and I thought it was finished. It was a much starker painting. It was basically my Grandfather seated in a chair in this huge empty space. The space was indicated by the line where the wall meets the floor, but there wasn’t green brocade cloth thrown over the chair’s arm, a plant, broken pottery or sweeping shadows and light. Home one weekend I discovered that he had reworked the canvas. I was in shock and couldn’t believe what he had done. When I asked why he said, “It revealed too much.”

I told that story to Eleanor Harvey, Curator of American Art at the DMA at the time. Eleanor had been a good friend to my father. Her response was comical…..sort of an, oh sure and he hid his feelings by adding an old plant and broken pots. Eleanor saw right through my father and in her beautiful essay she wrote for the show, “Barney & Martin Delabano” at the Tyler Museum of Art in 2001, she delivers an art history smackdown to my father, who always use to tell me that “it’s all about a brush full of paint being dragged across the surface of a canvas.”

“Portrait of Papa,” painted between 1970 and 1973, Barney tackled the complex task of representing his father and summing up their relationship shortly before”Papa’s” death in 1975. His father’s natural reserve and obscured past made Barney yearn to know more of this man, and by extension, himself. Dramatically, Barney painted his father because his parents had come to live with Barney’s family in 1968; psychologically, Barney painted him in an effort to penetrate the obdurate understanding of who “Papa” was.

Papa sits in a red chair, his posture and remote gaze conveying eloquently the emotional distance between father and son. The potted plant seems equally constrained, the mature plant tied to its support as the offshoot emerges independent of the parent plant. Yet the plants remain connected to the roots. the broken terracotta pot, evidence of previous attempts to nurture life and growth, provides its own commentary on the fragility of human relationships. Each compositional element is separate from the others, engendering a tension that is unresolved. In this portrait, Barney captured his father’s strength as well as his vulnerability, offering evidence of his father’s character without being able to pierce to its root. Frustrated by his inability to plumb his father’s depths and come away with satisfactory answers, Barney initially considered this painting a failure, refusing to look at it despite the fact that it hung in his home. Yet the portrait’s power derives from the very quality that once irritated the artist. It took time for Barney to see that he had, in fact conveyed the truth of his relationship with his Papa.”

Excerpt taken from Eleanor Harvey’s essay written in conjunction with the exhibition “Father and Son,” June 2001.

Wish my father could have read that about one of his pieces although he probably would have been embarrassed about it. At one point in my life I would have said, “Take that old man!”

My father was a figurative painter when figurative painting wasn’t cool. Not only was it figure painting, but it was also portraiture painting and that was certainly “old fashion” for the times. I remember people saying, “Why would you want to hang a portrait of someone you don’t know on your wall.” I don’t know, maybe because it might be a lovely painting or haunting in some way. Maybe it leaves you wondering….who is that person and why did someone want to paint a painting of them when it would have been so much simpler to just take a photograph.

Charles T. Bowling

Charles T. Bowling was the noted Texas painter who was living and working in Dallas when my father first moved here from Dennison Texas. He was included in the group called, “The Dallas Nine.” My father was sixteen and working at the White Star Laundry at Cole and Henderson, when a lady walked into the cleaners with her laundry. My father recognized the name and asked the woman, “Are you any relation to Charles T. Bowling, the artist.” Sadie Bowling told him that was her husband. My father told me that he told her that he too was an artist. Pretty brash thing to say for a sixteen year old to the wife of a important artist. Sadie invited my father home for dinner that night and they continued to feed him until he went into the service. My father spoke very fondly of the Bowling’s. My father came from a family that didn’t know anything about art and probably thought his wanting to be an artist was a misguided plan.

I’m betting at the time, the Bowlings were the family he wished he had been born into.

Otis Dozier

Otis Dozier was another member of the “Dallas Nine” and my father studied painting under Otis. Later in my fathers life he and Otis became friends.

I grew up getting to go over to Velma and Otis’s house as a child with my father. It was a wonderful house and studio. Otis had a walk-in, fireproof vault in his studio that held all his sketchbooks and Kachina Dolls. I remember thinking, now that’s pretty cool.

In their twilight years, Velma and Otis started inviting young artist over for pot luck dinners. I was lucky to be on their list as were other young artist. We would eat and then drink into the wee hours. They would tell us stories of the early Dallas art scene and about how they all got together to have artist parties. I remember being impressed that they told us that they played Surrealist games. Velma would always shame us for leaving so early…..1:30 AM. At 1:30 AM, Velma would still be smoking those cigarettes, tossing back bourbons and cursing like a sailor. Every young artist should be so lucky to share in those types of memories with older artist. It felt that as if Velma and Otis were passing the torch on to us. I am sure that my father felt the same way about the Doziers and Bowlings.

I guess my point in all of this is that we all have had people that have brought us into the world and there are those we’ve met and those we’ve sought out and they have all left their indelible mark on us. They have done this by lifting us up, making us try harder, by inspiring and mentoring us, and by their generosity they have made us the people we are today. I know that I had those people in my life and I am grateful. They have left me big shoes to fill and I will spend my life trying to do for others what others have done for me.

Thanks for this insight into you, your dad, and grandfather. It also demonstrates that artists cannot always comprehend the power of their own work.

LikeLike

Thanks David for your comment.

LikeLike

For me, this links back to “Anticipation and Trepidation…”

LikeLike